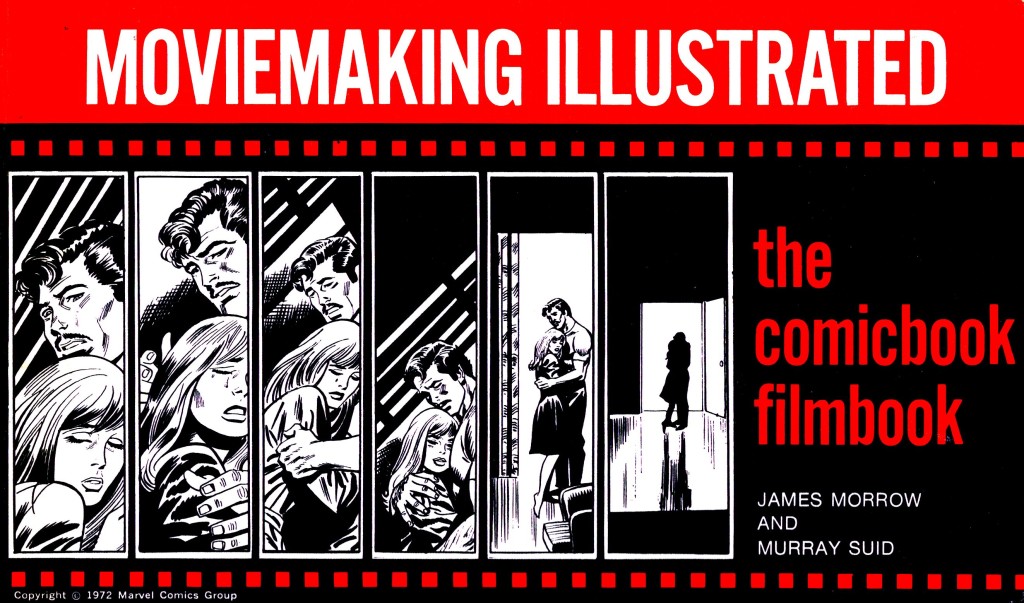

SUID: Why do kids like comics?

LEE: There are so many reasons. There’s the action, the color, the fantasy, the fairy-tale quality, the element of the unexpected. Comics give kids something they can’t get in other forms of media. They don’t get it in newspapers or movies or television

SUID: But doesn’t television supply fantasy?

LEE: Not the way a comic book does. The tube is more realistic. Take westerns or crime shows. They may be unreal in the sense that they’re romanticized, but everything is very realistically portrayed. When comic artists want something far out, we can draw the impossible. Television can’t photograph the impossible. So even fantasy-type shows like “The Six Million Dollar Man” are still very down-to earth.

SUID: You mentioned a “fairy-tale” quality in comics.

LEE: I think of our stories as fairy tales for people who have outgrown conventional fairy tales. Everybody in the world has loved traditional fairy tales as a young person. I think we all have a warm spot in our hearts for the Grimm or the Andersen stories, the Oz books, Br’er Rabbit, things like that. But when you get a little older—as you reach 10, 11, and 12—you don’t want your friends to see you reading “Cinderella” or “Little Red Riding Hood.”

Then suddenly you discover that comic books have what you’ve been looking for. Everything is bigger than life. There’s an element of magic. There’s a tremendous amount of fantasy running through them. Anything goes! And consequently, the reader is really getting the same type of pleasure he had gotten years before when he read “Jack and the Beanstalk.” He gets it in the comics. Where else can he go for that kind of entertainment?

Now I know that TV and movies also entertain kids magnificently. I wouldn’t knock either medium, both of which I love as much as I love comics. But with TV and film, the experience is fleeting. You see it once and it’s gone. A comic book, on the other hand, is a book. And the wonderful thing about a book or a magazine is that it has permanence. You can read it at your own pace, go back and reread it if you like, and then digest it or luxuriate in it as long as you wish. And the next day, you can read it again. Or if you’re not in the mood, you can put it aside and read it a little bit later. You can spend as much time with one panel as you wish. This is a luxury you simple can’t enjoy with theater, with TV, and with the movies. This is why comic books—and books in general—weren’t wiped out by the advent of television. Actually, the printed media are bigger than ever in recent years. The fact is, something you see fleetingly on the screen can never replace something you can hold in your hands and experience at your own pace.

SUID: You’re including comic books and real books in the same category.

LEE: They’re both literature. They belong together

SUID: You think kids read comics the same way they read a regular book?

LEE: I don’t just think it. I know it. Over the years, we’ve been swamped with letters from kids discussing the plots and writing style of our stories. There are almost no kids in the world who just look at the pictures. Even the five- and six-year-olds just learning how to read the words in our comics and write us letters about what they read and how they feel about it.

SUID: Still, don’t most people think of reading comics as being something different from reading real books?

LEE: Reading is reading. Someday I’m going on a crusade and I’m going to stump for comic books to be used in schools. Every time I pick up a newspaper and see the statistics on how the quality of reading is declining throughout the country, I want to devote myself to convince teachers that anything a younger wants to read has to be beneficial.

SUID: What makes you so sure?

LEE: We can tell from the letters we receive from both kids and parents. I think one of the greatest letters I ever received was from a mother who wrote that her son was valedictorian of his graduating class. She said: “I just want to tell you that he’s an honor student, and his father and I want you to know that the three of us have every reason to be proud of him. We do because we’re his parents, and you do because you’ve contributed so much to his education.” Imagine how I felt!

Every day we get mail from teachers saying that our books are used in a range of courses—from remedial reading to contemporary literature. They even say that the vocabulary in our comics is better than that found in some of the standard junior high readers, the words are more adult. The teachers are just delighted because the kids have advanced their vocabulary by reading comics.

We never reject a word because it might be over the head of the reader. If a story calls for a word like “radiation” or “subliminal,” we’ll use it because we feel that the younger reader will absorb it by osmosis, or he’ll look it up. We get letters from kids in disadvantaged neighborhoods, written in the vernacular, so to speak, and these kids will throw in a word like “cataclysmic” that they’ve seen in one of our comics.

SUID: I’m surprised that you give so much attention to the verbal part of such a visual medium.

LEE: I love words—the sound of them, the flavor of them. I love the rhythm of the words in the Bible. I love the way Shakespeare used words—“What ho, Horatio.” I try to get that flavor in stories like “Thor.” When I first started writing comic scripts, my colleagues thought I was crazy. I’m a very fast writer but I might stop and spend ten minutes looking for the right word. I like to think that anything I write will sound good when it’s read aloud.

SUID: Do teachers ever tell you that they read your comics aloud in class?

LEE: Very often. Not only in class, but disc jockeys will read them over the radio. Many English professors have told me that they can as poetry. They ask: “Do you intentionally write dialogue balloons as prose poetry?” And I do try to get a rhythm in the writing. Otherwise, it’s too much like a textbook. When you read for entertainment, the words should flow and the rhythm should be right.

SUID: Do you think this is why kids like to read comics?

LEE: One of many reasons. When I have Thor say, “So be it” instead of saying, “OK,” the kid reacts positively because he’s aware of the dramatic language. He enjoys reading. And that’s the point. Enjoyment. Reading a well-written comic book can be the most beneficial thing in the world. You read them on two levels. If you’re already a literate person, you’re reading them for enjoyment. If you are not literate, you’re reading them for enjoyment but you’re also learning how to read.

If our comics were given to every kid from kindergarten up, I would be greatly surprised if the reading ability of students didn’t improve one hundred percent. Of course, librarians and teachers might not see it this way. If you’re an educator or an educational publisher, you’ve got to think that textbooks are more influential than cheap volume literature, or, as they think of it, “newsstand sensational material.” But what they don’t see is that comics can be a bridge for alienated kids.

Take ghetto kids, for example. I have gone into areas where there are black kids who are very hostile to whites. And I’m a hero to them. They say, “Hey man, tell me about Spider-Man.” They feel comfortable with me. And it is through the comic book that I have reached them

SUID: Textbook producers often try out their stuff with kids. Do you?

LEE: No. Never. The minute you reduce it to a science, like writing textbooks, you’ve lost something. We don’t control vocabulary. We don’t field-test. We don’t slant our stories. And kids go out and buy our books. How many textbooks would they go out and buy? Of course, the pictures help them enjoy the words. They are the fronting on the cake.

SUID: But don’t the pictures act as a crutch, and maybe even stop kids from taking the words seriously?

LEE: Your question reminds me of one thrown at me by a woman in the audience at one of my speaking engagements. She thought it was bad for her daughter to read comics because it would stop her from using her imagination. I asked her if her daughter’s imagination would be harmed if she attended a dramatic presentation of a play by Shakespeare. There you have a marriage of words and visuals. Of course, it doesn’t harm the imagination! I think our comics should be compared to such an experience. I am not a snob and I don’t turn up my nose at any form of culture. I consider pop music as beneficial as classical music. I consider comic books as beneficial as the works of Charles Dickens. I wouldn’t put myself in the same class as a writer as Charles Dickens. For all I know, I’m better. Of course, not every story in the Marvel comic series ranks with Oliver Twist.

LEE: Years ago, comics were written by people who weren’t really good writers. Now we’re trying to make them totally different. We have writers whoa re former English teachers. Some also write novels. We have the finest artists in the world. There certainly is nothing wrong in telling a story with pictures and dialogue balloons. It’s like a play or movies or television—except that you have less space to say your piece so you have to be more concise. Mario Puzo, the author of The Godfather, once tried to write a comic-book script for me. A month later he said, “Stan, forget it; it’s too difficult. In the time it would take me to do this, I could write a novel.”

SUID: Are you saying that comics ought to be taught like literature?

LEE: They are literature. A guy playing a kazoo is playing music, don’t you see? And comic books are books.

SUID: Do you try to deliver a moral lesson with your stories?

LEE: Some people think I take myself too seriously, but I have to. I’ve had so much mail over the years from parents and teachers who say, “Do you realize how influential your books are with young people?” Consequently, I have become hypersensitive about keeping out of the books anything that might be harmful. Sure, we’re trying to entertain, but while entertaining we don’t want to teach any values that might not be good values. We’re very careful.

SUID: What about violence? Do you get condemning letters about that?

LEE: Our comics are not violent. Sure, they have a lot of fighting and action. Fistfights. The kind of fistfights we have in our comics is not different from those in King Richard the Lion-Hearted Fighting the Crusades. You’ve got to have conflict. Good vs. evil. There has to be the giant saying, “Fe fi fo fum” and chasing Jack. That’s not violence. The real violence in the world is bigotry, war, hatred. We have a character named Dr. Doom. He’s one of our top villains, always scheming to take over the world. They can’t throw him in jail because there’s no law against trying to take over the world. If he were a litterbug or a jaywalker, he could be sent to jail. But he can’t be arrested for trying to take over the world.

SUID: Comics really teach values then?

LEE: Yes, in a non-preachy way. The minute you start to lecture kids you’ll turn them off. The same is true in schools. Students would love school if they were forbidden to go. But because they’re forced to go, the teacher has a tremendous problem. The student walks into the class resenting the teacher. What the teacher needs is to know how to communicate. Teacher training should include practice in communication. Teachers have to make the kids want to be in their presence. The most important thing is not to be dull.

SUID: Do you have nay advice for teachers about comics?

LEE: Yes. Use them like crazy. Use them all you can

SUID: How?

LEE: I’ll leave that to you.

# # #

As a sidebar to the interview, Learning Magazine developed a series of activities meant in response to Stan Lee’s challenge that teachers “use comics like crazy.”

HOW TO USE COMICS LIKE CRAZY

Photo comics

Many kids, especially those who feel relatively confident with a pencil get great satisfaction out of creating their own comic books. If you have access to a camera and some film, even those who feel they can’t draw can join in my making photo comics. (In Europe, many professional comics are done this way.) The first step is plotting out a story that can be told in 1 or 20 parts—depending on the number of shots on your roll of film. Assemble props, costumes, etc. As children perform, the teacher or other children photograph the action. Large gestures work best. When the prints are returned, glue the shots onto stiff paper, print dialogue and narration on a separate sheet, cut them to fit the panels, and then glue them onto the photos. A 12-shot comic in black and white will cost about $3.50, assuming all the shots come out.

Last century, major writers like Dickens published their works as serials. In the 1940s, radio and move serials were the rage. Now comic books and comic strips are the major form of serialization. Comic serials give kids a chance to match their plot-making wits against the pros. Pick a monthly comic with a continuing story and have students pick up the action themselves. When the next installment appears, kids can compare their continuations with that of the pro. (Don’t be surprised if they like their own versions better.

Comparative literature

Marvel Classics Comics retell some world famous literary works. Have old students compare the comic treatment with the original. Which parts were left out? Why? Was anything added? Does the story lose—or gain—in translation? Which version would the student recommend? In some cases you might find a story that’s been translated into film as well as comics. If the story appears on TV—as many classics regularly do—the students can do a three-way comparison.

Comics as scripts

With a little bit of fussing, comic books can serve as play scripts. (Indeed, some Broadway plays, like You’re a Good Man, Charlie Brown, draw heavily on comic-strip material.) The dramatic dialogue is found in the balloons. The pictures plus the narration suggest the action. Some creativity will be required to simplify the staging, since most action comics leap about from setting to setting with great abandon.

For simplicity,, you might suggest that kids create scripts for tape-recorded “old-time radio shows.” With this format, concern over costumes, sets, lighting, etc., are eliminated. But since the play with be totally aural, visual material must be converted to words and sounds.

A variation of this activity has older kids reading comics aloud to younger children. While one person can read all the comic parts, it may be more dramatic for several older children to do a kind of redaders’ theater—one taking the narrator’s lines, another making the sound effects, and two or three others reading the dialogue found in the dialogue balloons.

You may want to have the students tape-record such a reading. The trick is to number each panel so that the younger kids can more easily follow along. Naturally, this will work best with relatively simple comic books.

Translating comics

Just as novels are often made into movies, and movies sometimes made into novels, comics can be translated into short stories. Challenge students to come up with their own all-prose versions of a given comic book. The task will require writing prose passages that convey information found in the comic’s visuals, using quotation marks instead of dialogue balloons, adding dialogue tapgs (“he said with a sneer,” “she whispered”) and so on. Even starting with the identical swtory, each student’s version will probably be distinctive, since any kind of translation or adaptation involves osme measure of creativity. Students can gain real insight into this process by comparing their various efforts.

Listening to the lingo

Comic-book dialogue tends to be less literary and more folksy than dialogue found in short stories or novels. It uses more slang, and also attempts to convey quirks of speech through a vasriety of typographic techniques. Kids might study the way speech is presented in comics, and then do some speech-listening research to see if comics capture the way people really talk. They then can use comic dialogue devices themselves in conveying real speech found in their own homes.

Comic critiques

As an antidode to the=name-of-my-book blues, suggest kids review comics books instead of regular books. There is nothing frivlous in thie assignment. Comics present the double-barreled challenge of evaluating both prose and art. The first step is to determine criteria. In considering the art, students might discuss cover design, color, clarity, and so on. As for the text, there are all the traditional literary elements: plot, characgterization, theme, and narration. Dialogue probably demands special attention, since comics, in essence, are a form of drama on paper. For models of comic criticism, students can study the letters section found at the back of most comics. Here, readers send in their comments on all aspects of past issues.

Theme analysis

Recognizing the theme of a work is a fundamental literary skill. Usually the theme can be stated in a few words—“Crime does not pay” or “It’s good to be strong.” Aesop’s fables make a good starting point for theme analysis since the themes are articulated as the “morals.” (Of course, different people may find different themes in the same work.) Once the kids get the notion of what a theme is, let them try picking out themes froma variety of formats: comic books, comic strips (“Peanuts” is especially thematic), poems, movies, TV shows, and even commercials. Then have them compare the kinds of themes hadnled by each format; that is, do adverture comic books have the same or different themes as action TV shows?

# # #

Previous post

Previous post

Next post

Next post